From 12 – 18 of November, members of Bertha’s Be Just Network visited Bertha partner CCAJAR in Colombia to learn and exchange experiences about their education programs for law students, junior lawyers, grassroots initiatives, indigenous communities and trade unions. The delegation included lawyers and educators from Bertha Foundation (UK), Center for Applied Legal Studies (CALS, South Africa), Earth Rights International (ERI Thailand), European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR, Germany) as well as the Proyecto de Derechos Economicos Sociales y Culturales (ProDESC, Mexico).

The trip was a wonderful and enriching experience: so great, that we want to share it with you!

On the first day, we met law students, members of the CCAJAR school of legal assistants, who are trained on the job how to litigate strategically to hold the highest-ranking state officials and private actors responsible for crimes that include forced disappearance, extrajudicial killings and torture. These crimes continue today, while Colombia is on the verge of hopefully signing a peace agreement with the largest active guerrilla group, FARC. We were impressed by the passion and commitment that these students bring to their work.

Next, we stopped over in Popayan, departmental capital of Cauca, in the south west, to visit CCAJAR’s school of legal facilitators. They invite leaders from different grassroots initiatives, indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities and trade unions, to be trained on the legal defence of their land and territories. They receive training on their constitutional rights, how to claim them in court, on the basics of environmental legal principles and on practical questions of gathering evidence or campaigning. Participants who had participated in a four-month online course and who have fulfilled the necessary work assignments, came together at an ecological resort outside of Popayan, for a five-day-workshop.  They will “graduate” as legal facilitators and will serve as multipliers in their communities. During the course, they exchanged experiences and learned from each other about issues such as communal environmental monitoring and took part in various practical exercises. For example, they all attended meetings with public authorities, many of them for the first time ever, to learn by doing lobbying and advocacy work.

They will “graduate” as legal facilitators and will serve as multipliers in their communities. During the course, they exchanged experiences and learned from each other about issues such as communal environmental monitoring and took part in various practical exercises. For example, they all attended meetings with public authorities, many of them for the first time ever, to learn by doing lobbying and advocacy work.

The next day, we had the opportunity to meet Feliciano Valencia, an indigenous leader of the NASA group of Cauca. He is serving a sentence of 16 years imprisonment in an indigenous “harmonization centre”. Instead of punishing offenders, it is a place where prisoners work spiritually to harmonize themselves with nature and with their community. Why is Feliciano there? He was unjustly sentenced by the state justice system for kidnapping. In 2008, during a peaceful demonstration in defence of their land rights, the indigenous community to which he belongs, had decided collectively to apply indigenous justice – a system recognized by and protected under the Colombian constitution – to a soldier who had infiltrated their demonstration in an attempt to plant false evidence that would have slandered the community as being connected with the guerrillas. The Colombian state did not accept their exercise of indigenous justice in this case. But instead of initiating a procedure to resolve conflicts of jurisdiction, they accused the community’s leader, Feliciano, of kidnapping the soldier. When we met him, we were  impressed by his personality: he is a friendly and generous man, upright and humble, wise and extremely clear in what he has to say; a man who thinks of the well-being of his community and of all Colombians. Although unjustly imprisoned, he is committed to the spiritual exercise that is practiced in the seclusion center, in order to contribute to harmonization and peace. We said goodbye to him, impressed but also very concerned: the night before our visit, and just a few days after Feliciano had been transferred to the center, several armed men, not members of the indigenous reservation, intruded onto the farm and approached the center in the middle of the night – how else could we interpret this than an attempted attack against the life and security of Feliciano? Fortunately, the indigenous guard prevented the attack at the last minute. CCAJAR is planning to bring Feliciano’s case of unjust imprisonment and of the risks he faces in detention to the Inter-American Court.

impressed by his personality: he is a friendly and generous man, upright and humble, wise and extremely clear in what he has to say; a man who thinks of the well-being of his community and of all Colombians. Although unjustly imprisoned, he is committed to the spiritual exercise that is practiced in the seclusion center, in order to contribute to harmonization and peace. We said goodbye to him, impressed but also very concerned: the night before our visit, and just a few days after Feliciano had been transferred to the center, several armed men, not members of the indigenous reservation, intruded onto the farm and approached the center in the middle of the night – how else could we interpret this than an attempted attack against the life and security of Feliciano? Fortunately, the indigenous guard prevented the attack at the last minute. CCAJAR is planning to bring Feliciano’s case of unjust imprisonment and of the risks he faces in detention to the Inter-American Court.

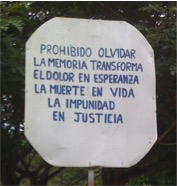

Further north, in the Valle del Cauca Department, we visited the association of family members of victims of State crimes, AFAVIT, in a place called Trujillo. This village has seen more than 300 crimes and massacres in the years 1986-94, committed by drug cartels and paramilitaries with the collaboration of the State. The Colombian state has been sanctioned by the Inter-American Court for these crimes and a former Colombian President has asked for forgiveness. The community is an example – at national and international level – for their efforts in constructing collective memory:  “memory transforms pain into hope, death into life and impunity into justice” says one of the many signs in the Memorial Park that they built with the reparations from the Inter-American Court. They continuously develop the park further because further crimes continue to be committed every day. Up until today, many victims have not been recognized, many have not received reparation and many are still waiting to get their land back – having been forcibly displaces. And, what struck us most: the Memorial Park has been defiled various times, the last time just a month ago and its founder has been killed. The members of AFAVIT can teach us how being a victim does not necessarily mean to be passive and defenceless: for them, being victims have united them into collective action as a way to survive, to recuperate their lives and their dignity and to build community for a peaceful future.

“memory transforms pain into hope, death into life and impunity into justice” says one of the many signs in the Memorial Park that they built with the reparations from the Inter-American Court. They continuously develop the park further because further crimes continue to be committed every day. Up until today, many victims have not been recognized, many have not received reparation and many are still waiting to get their land back – having been forcibly displaces. And, what struck us most: the Memorial Park has been defiled various times, the last time just a month ago and its founder has been killed. The members of AFAVIT can teach us how being a victim does not necessarily mean to be passive and defenceless: for them, being victims have united them into collective action as a way to survive, to recuperate their lives and their dignity and to build community for a peaceful future.

In Cartago, our next stop-over, we met the School of Environmental Thinking, a grassroots initiative of citizens who through popular education, arts, and political protest have been able to build environmental awareness in a town that has a long history of domination by drug cartels and paramilitaries. Members of the school have participated in CCAJAR’s legal facilitators’ training: you can tell from the way they channel their commitment and passion into strategic legal and political action, combined with educational and artistic actions.

Back in Bogotá, we learned about CCAJAR’s security situation: the story is a very long one that dates back many years. It peaked during the period of ex-President Uribe, when the former state intelligence service DAS put together an observation file on each of the organization’s members: they documented where CCAJAR are and when, who they meet with, what they like to eat and how they spend their free time, who their family members are, where their kids go to school. They tapped their mobile phones and emails. There are indications that some of the worst death threats can be linked back to this State institution. Just one example: one of the lawyers, a mother of a daughter, was sent a baby doll, dismembered, coloured in red in the genital area to indicate a violation, with a note saying “you have a beautiful family, take care of it, don’t sacrifice it”. The current strategy against the Lawyers’ Collective is to use false testimony and smear campaigns to discredit them as fraudulent, corrupt, and enriching themselves at the cost of their clients, who are victims of human rights violations. Legally, these accusations have no foundation: but this is why these attacks are waged through media campaigns that can do harm, despite being based on lies. They provoke and serve as justification for physical attacks that might follow later, as we have seen in many similar cases of human rights defenders in Colombia.

it”. The current strategy against the Lawyers’ Collective is to use false testimony and smear campaigns to discredit them as fraudulent, corrupt, and enriching themselves at the cost of their clients, who are victims of human rights violations. Legally, these accusations have no foundation: but this is why these attacks are waged through media campaigns that can do harm, despite being based on lies. They provoke and serve as justification for physical attacks that might follow later, as we have seen in many similar cases of human rights defenders in Colombia.

In spite of all this, the ideas of CCAJAR, which was founded 37 years ago, grow and spread –several similar organizations made up of former CCAJAR-trained students have developed over the years and now conduct similar work in Bogotá and other regions of the country.

CCAJAR is an exemplary organization in and for Colombia: their human rights work in the courts and their education programs empowering communities, students, trade unionists and lawyers, is remarkable, courageous and deserves admiration. What CCAJAR needs, in order to continue its important work, is international solidarity and support – so: write your messages of support here!

Thank you, CCAJAR, for your generous sharing, for teaching us, for doing the work you do and for never stopping!

For more information see www.colectivodeabogados.org and follow their work on Twitter @CCAJAR.

See also an award-winning film on their work here! (Spanish)

Annelen Micus, former Bertha Fellow at European Center for Constitutional Rights, ECCHR, now working as a legal advisor at Colectivo de Abogados, José Alvear Restrepo, CCAJAR

Follow Annelen on Twitter @Annelen_Micus

Claudia Müller-Hoff, Human Rights Consultant, European Center for Constitutional Rights , ECCHR

Follow Claudia on Twitter @hoff_claudia

Article Tags: Bertha Fellows / CCAJAR / Colombia / Human Rights / human rights lawyers / movement lawyering