BALTIMORE’S HOUSING LEADERSHIP SCHOOL

Based in Baltimore, Maryland, the United Workers Association is a statewide organization of low-wage workers who are organizing for better wages and working conditions. In 2008 they launched the Fair Development Campaign, which focuses on housing and recognizes that development must address all economic, social, cultural, and environmental aspects of people’s lives in a way that increases communities’ ability to meet their fundamental needs. Through this campaign, they joined forces with other local organizations to coordinate the Baltimore Housing Roundtable’s Leadership School, which works to train and consolidate a group of leaders to understand the systemic issues underlying the current housing system, and then prepare these leaders to build the campaign for change. A grant from the Bertha Foundation enabled the United Workers Association and the Baltimore Housing Roundtable to expand their course offerings to include entry level and more advanced options.

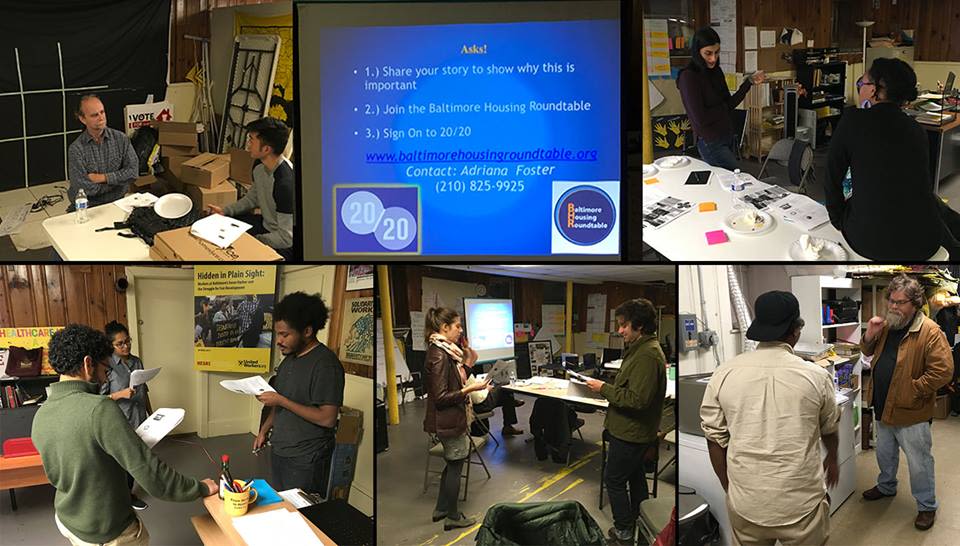

United Workers and the Baltimore Housing Roundtable’s Leadership School recently wrapped up our Fall semester of courses, where for the first time, our Fair Development Leadership School included linking together issues of work, housing, and environmental sustainability, and we were also able to begin a higher level course on community land trust collaboration. We ended the year with the first in a series of “train the trainers” sessions on our 20/20 campaign, which works to secure public investment in permanently affordable housing, jobs, and urban agriculture.

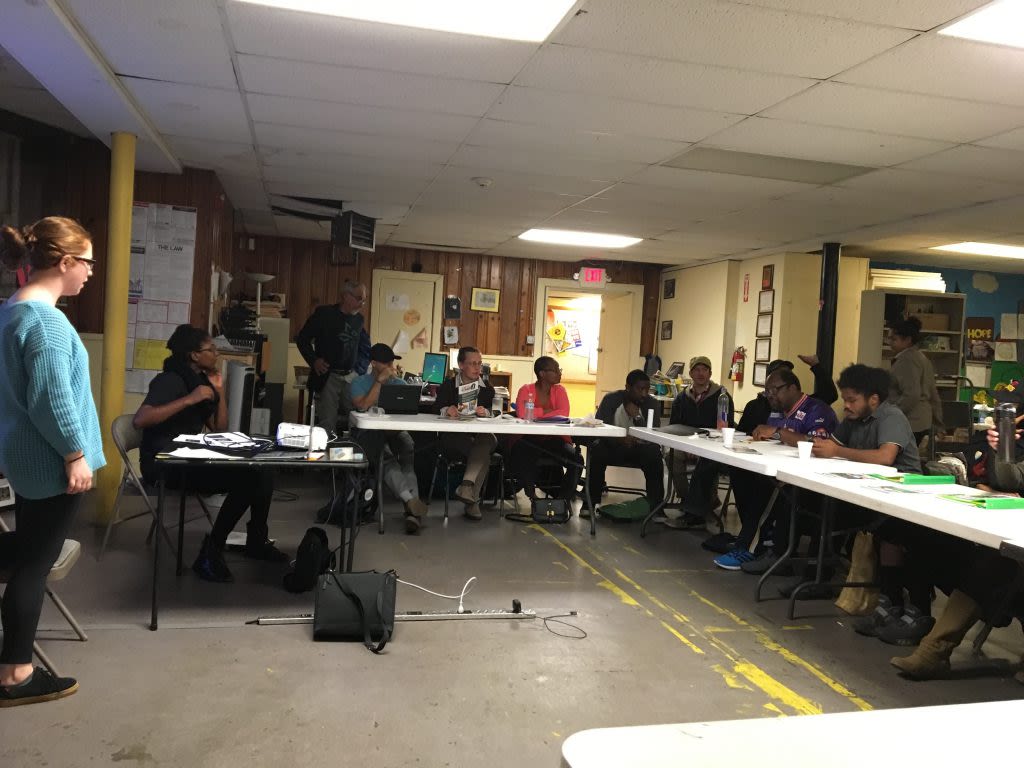

Bringing together human rights organizing at the Fair Development Leadership School meant creating a multi-issue curriculum that reflected Baltimore’s history and political economy, and challenged notions of power and powerlessness. Students came from all walks of life, from homelessness to being a student at Johns Hopkins University, and included residents from all corners of Baltimore.

The first workshops of the ten-week school examined how Baltimore and the United States haven’t lived up to their promises, and instead often succumbed to private economic interests, and systemic racism that has increased inequality. We studied how Baltimore ‘s practices of whites-only restrictive housing covenants and “block-busting” precipitated white flight to newly built suburbs and a decline in restricted black neighborhoods. We reflected on how as the economy shifted from a manufacturing base to a service base, city policy subsidized that shift by spending over $1 billion on low wage services jobs at the Inner Harbor waterfront. This shift and its inability to expand equity particularly to Black and Brown communities has catalyzed our call for a new Fair Development model meant to first meet people’s basic needs. Here is an interactive timeline of Baltimore political, economic and environmental history we developed for the course.

To this end we studied power and powerlessness and particularly invisible power (the power of ideas and beliefs). We reflected on the need to combat stereotypes about the poor and decades of “welfare queen” mythologies and even today’s era of fake news perpetuated on social media, and on the need to tap into core human rights values that life has dignity, and that all should have the right to breath clean air or live healthy lives despite the zip code they happen to come from.

“My name is Destiny Watford. I live in Curtis Bay, a tight knit community in South Baltimore. It is my home and I love it but Curtis Bay is pollution central. Anyone who has been to Curtis Bay knows that. Largely due to the industrial area surrounding it, Curtis Bay is not the healthiest place around. In fact, we discovered that Curtis Bay, although it is a rather small community, is one of the most polluted areas in the state. We also know that people die in Curtis Bay of lung cancer, heart disease and lower respiratory disease at some of the highest levels in the city of Baltimore. All of this is enough to make it feel like the community’s fate is to be dirty and polluted. But when we learned about a plan to build the nations’ largest trash burning incinerator less than a mile away from our school – we were still shocked.

We know that our lives matter just as much as anyone else’s. We know that we have a right to a safe and clean environment and that our lives should not be limited by asthma or cancer just because of where we were born. We have a right to Fair Development that puts the health of all communities first.”

— Destiny Watford, United Workers youth leader, and student in most recent Fair Development Leadership School, and last spring, recipient of the international Goldman Environmental Prize.

At the end of the 10-week course we launched a series of “train the trainers” sessions on the 20/20 campaign with our graduating class. These sessions focused on building capacity for our campaign that calls on Baltimore city to invest annually $40 million in community-driven development for permanently affordable housing, jobs and environmental sustainability. Leaders are going to be organizing a public campaign in their neighborhoods, and faith communities and union halls are building support for this initiative. We are also forming a team to document systemic displacement and create a series of tribunals to raise up the voices of those most impacted by this economic crisis. Our end goal is major public investment by Baltimore’s Mayor and City Council in 2018.

While we build leadership capacity we are also growing capacity among our network of community land trusts. To ensure we are able to scale up and sustain community land trusts in Baltimore, we are facilitating a leadership school that focuses land trust leaders on the question of building an infrastructure to share capacities where possible and retain autonomy where necessary. This is called a “central server model” that looks to increase sustainability by centralizing certain core functions all land trusts must do (ex. accounting, tax filing, fundraising, housing counseling, standardizing ground leases); and recognizing what tasks should be left at the neighborhood or individual land trust level (community planning, development priorities). We held our first all day session this past August which was co-facilitated by the national community land trust organization, Grounded Solutions. 18 representatives from several land trusts in operation and several in a start-up phase attended this school. After sharing their vision for community development specific to their land trust, there was widespread agreement to initiate establishing an information “hub” to share technical assistance documents such as business plans, bylaws, fundraising research and so on. This has since been established and there is now work being done to establish a common ground lease and collectively develop relationships with financial partners, including local banks.

More sessions at this level are being planned for 2017, and a Spring Semester Fair Development Leadership school is also being developed.

CREDITS

Todd Cherkis, Leadership Organizer, United Workers

Follow United Workers on Twitter @unitedworkers, on Facebook @unitedworkers, and learn more at unitedworkers.org.

Originally published: January 26, 2017

Built with Shorthand

Built with Shorthand