In this blog, legal intern Geeta Koska reflects on her experiences researching the use of pesticides and resulting human rights violations in India. She worked as part of an international team of lawyers and researchers seeking to hold European companies to account for major health problems caused by their products, led by the Bertha Justice Initiative Network partner, the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights.

Pesticide use in Punjab, India

Most pesticides used in India find their way onto the fields of the northern state of Punjab, the country’s bread basket. Their current indiscriminate use has been linked to rising cancer rates, reproductive disorders, as well as huge debts and increased numbers of farmer suicides across the state.

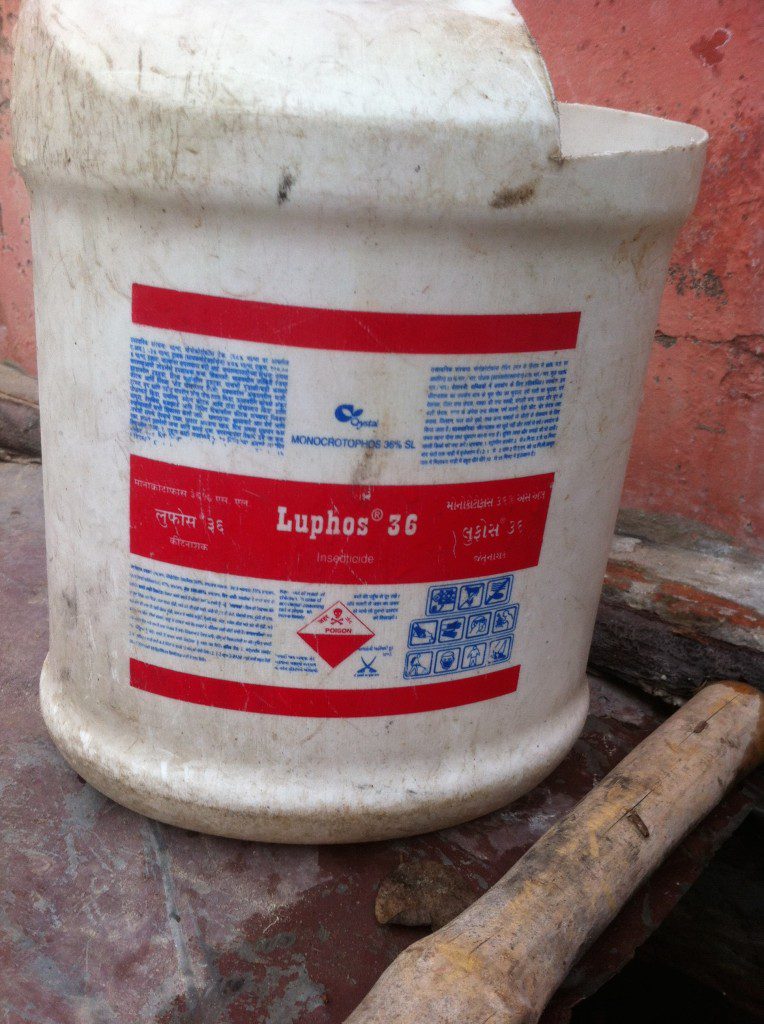

One of the reasons for this adverse impact is that there is no proper training for farmers, pesticides are not properly labelled and their use is not suitably monitored. As highlighted in a report submitted by a coalition of NGOs in 2015, the German and Swiss companies Bayer and Syngenta fail to adhere to international standards on pesticide management. Moreover, double standards in the pesticide industry mean that while Bayer warns European users that the hazardous pesticide Nativo 75 WG is “suspected of damaging the unborn child”, no such warning is given in India.

To hold European pesticide companies to account for their double standards, it’s necessary to understand the impact of their operations abroad and so I spent three months in India researching this issue and exploring potential legal challenges to stop this practice.

Conducting inquiries in Punjab

During my research, I was very aware that international inquiries often happen within a context of global inequality and there is a danger of reinforcing imbalances of power. Focusing almost exclusively on countries in the Global South, Obiora Chinedu Okafor argues that human rights fact-finding by people from the Global North can reproduce the association of North/South as Good/Bad. Others have criticised international fact-finding for being an elite activity, typically carried out by privileged western “experts” who exploit people to promote their own agenda. Coming from London to India to research how pesticides are used and distributed, I unavoidably carried some of the baggage associated with international inquiries with me.

As a young researcher, I had much to learn – from what to wear to how to communicate via interpreters and overcome this North/South divide. The apparent differences between those I interviewed and myself complicated this; my gender, educational background, and the fact that I grew up in a city were potential barriers to understanding people’s issues and concerns when conducting interviews. Language and literacy further complicated the research, as the instructions on pesticide bottles could not be understood by some of the pesticide users I interviewed. As a result, conducting the inquiry and engaging with interviewees without strengthening a negative narrative was a real challenge.

Related to this was the difficulty in obtaining information that was sufficiently rigorous to be used in legal proceedings without leaving participants feeling exploited. For instance, some pesticide users found it hard to explain exactly when a symptom started or which brand of paraquat they used. This was often because symptoms reoccur and people have learned to deal with the acute side effects of pesticide exposure without access to proper medical help. Others did not necessarily know the name or brand of the pesticide they have been exposed to because they relied on distributors for information on which pesticide to use on crops. In the course of the inquiry, I found that it was important to be aware of the specific context and of the potential risk of disempowering participants in the course of the interviews.

Lessons learned

Although I do not have all of the answers to the complex issues that surround the conduct of international inquiries, my experience provided insight into ways of overcoming some of the issues raised.

First, to overcome the potential of reinforcing hierarchies between those interviewed and myself, it was important to look at the broader social and economic context. For example, though obstacles to access to education in rural parts of Punjab exist, illiteracy was not always the reason why users could not understand instructions. In fact, closer scrutiny revealed that in some cases instructions were printed too small for users to read, and lack of training meant that users were unaware of the meaning of the hazard symbols on bottles.

Second, I had to look back to the North to understand human rights violations that occur in the South. This is particularly relevant when investigating corporate-related human rights violations, as it is necessary to follow the supply chain back. Therefore, during the interviews, it was important to shift the focus from local conditions to the responsibilities of the companies that produce the pesticides that are sold in India.

Because of the international element of the issue – the companies that produce the pesticides are mainly based in Western Europe – international researchers have to work in partnership with national lawyers, researchers and NGOs to gather evidence. As a legal intern on the team I encountered some of these risks and learned to remain vigilant to the challenges that can arise during international inquiries. My time in India introduced me to new ways of understanding global issues as well as different methods of working, which I will be able to put into practice through the rest of my career.

Geeta Koska worked on Business and Human Rights at the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) in Berlin via their Education Program.

Geeta Koska worked on Business and Human Rights at the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) in Berlin via their Education Program.

Follow Geeta on Twitter: @koskageeta